On this page:

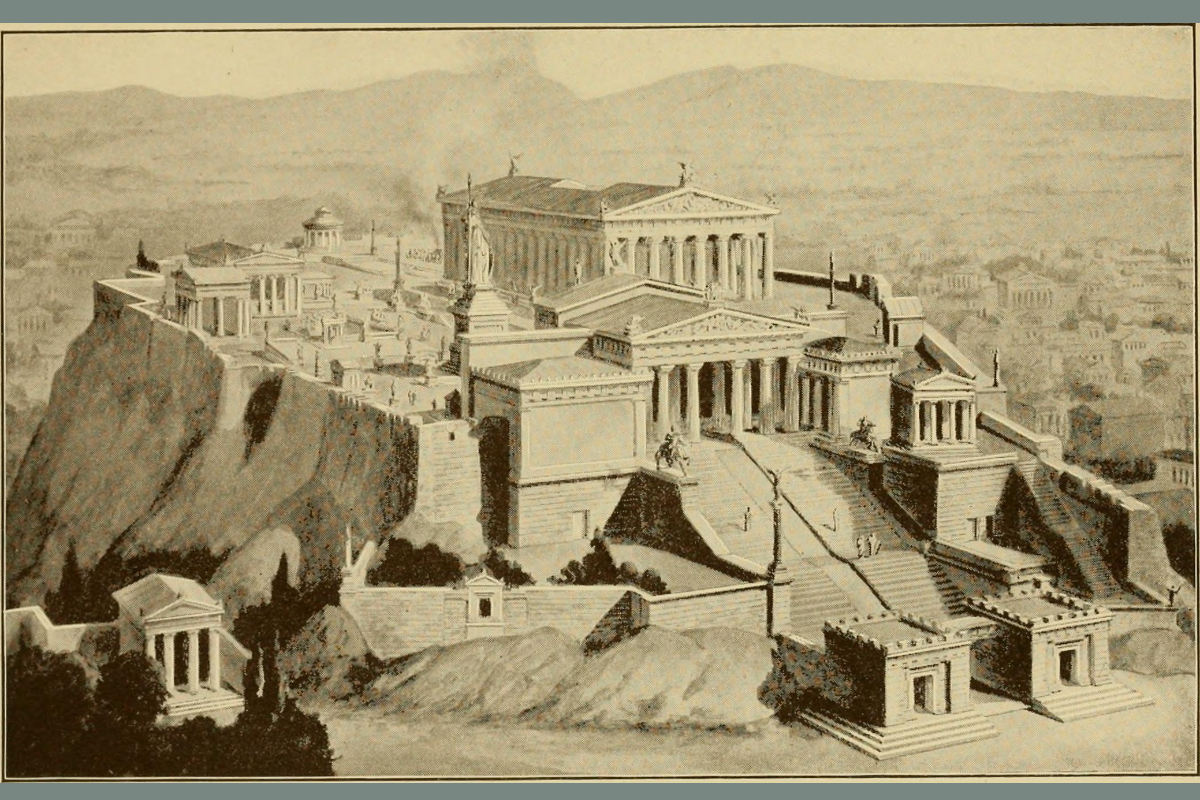

Ο Παρθενώνας (Parthenon), is an Ancient Greek temple in the Acropolis of Athens, dedicated to Athena Pallas or Parthenos (virgin). It is widely considered to be the pinnacle of Classical Greek architecture, and over the years it has become the trademark image of the entire civilization.

The classical Parthenon visible today was constructed between 447-432 BCE as the focal point of the Acropolis building complex by the architects Iktinos and Kallikrates (Vitruvius also names Karpion as an architect).

The temple’s main function was to shelter the monumental statue of Athena that was made by Pheidias out of gold and ivory. Temples in Greece were designed to be seen only from the outside. The viewers never entered a temple and could only glimpse the interior statues through the open doors. The temple and the chryselephantine (made of gold and ivory) statue were dedicated in 438, although work on the sculptures of its pediment were concluded in 432 BCE.

Earlier foundations under the Parthenon indicate that the Athenians had began the construction of a building before they were interrupted by the Persian invasions who destroyed the incomplete building in 480 BCE.

Not much is known about this earlier temple, and even the state of its construction when it was destroyed has been disputed. Its massive foundations were made of limestone, and the columns were made of Pentelic marble, a material that was utilized for the first time. It was presumably dedicated to Athena, and after its destruction much of its ruins were utilized in the building of the fortifications at the north end of the Acropolis.

As a temple, the Parthenon’s main function was to provide shelter for the monumental chryselephantine (gold and ivory) statue of Athena. A temple in Ancient Greece was literally “the house” of the deity/ies it was dedicated to, and the statues inside them were considered to be the presence of the deity.

The Parthenon also functioned as the city’s treasury.

The Parthenon Architecture

The Parthenon is a temple of the Doric order with eight columns at the façade, and seventeen columns at the flanks, conforming to the established ratio of 9:4. This ratio governed the vertical and horizontal proportions of the temple as well as many other relationships of the building like the spacing between the columns and their height.

The cella was unusually large to accommodate the oversized chryselephantine statue of Athena, confining the front and back porch to a much smaller than usual size. A line of six Doric columns supported the front and back porch, while a colonnade of 23 smaller Doric columns surrounded the statue in a two-storied arrangement that made the interior space seem even larger and taller than the exterior.

The statue of Athena Pallas reflected its immense stature on the tranquil surface of the water-pool that covered the floor.

The placement of columns behind the statue was an unusual development since in previous Doric temples they only appeared on the flanks, but the greater width and length of the Parthenon allowed for a dramatic backdrop of double decked columns instead of a wall.

The back room faced west and sheltered Athena’s treasure. The doors that lead to the cella were abundantly decorated with relief sculptures of gorgons, lion heads and other bronze relief ornaments. Four columns of the Ionic order supported its roof.

It is noteworthy that the Parthenon architects employed both Ionic columns in the interior, and an elaborate continuous Ionic frieze on the exterior wall of the cella.

While the integration of Doric and Ionic elements on the same temple was not a new development in Greek architecture, it was rare, and bestowed on the Parthenon a delicate balance between austere and ornate visual characteristics.

The Parthenon has no absolute straight lines, giving the structure a subtle organic character despite its obvious geometric disposition.

The columns of the peristyle taper on a slight arc as they reach the top of the building giving the impression that they are swollen from entasis (tension) – as if they were burdened by the weight of the roof; a subtle feature that allots anthropomorphic metaphors to other wise inanimate objects.

The peristyle columns are over ten meters tall, and incline slightly towards the center of the building at the top (about 7 cm), while the platform upon which they rest bows on a gentle arc which brings the corners about 12 cm closer to the ground that the middle.

The architects of the Parthenon have been credited as being excellent scholars of visual refinement, an attribute undoubtedly sharpened by years of architectural development and observation of the natural world.

They designed the columns that appear at the corners of the temple to be 1/40th (about 6 cm) larger in diameter than all the other columns, while they made the space around them smaller than the rest of the columns by about 25 cm.

One of the accepted reasons for this slight adaptation of the corner columns claims they are set against the bright sky, which would make them appear a little thinner and a little further apart than the columns set against the darker background of the building wall. The increase in size and decrease of space thus compensates for the illusion that the bright background would normally cause.

Careful observers would notice that the corner columns’ placement breaks the established pattern of centering each column under every other triglyph.

While puzzling in a building obsessed with strict logic and precision, it is perhaps a glimpse at Greek practical thinking: If the pattern of aligning columns under every other triglyph is followed too strictly, the center of the last column in the sequence would always fall almost exactly under the very corner of the entablature. This is called “The problem of the corner triglyph”.

This would not only look aesthetically awkward, but would present static problems as parts of the corner column would nor be weight bearing.

So, it seems logical that logic was altered just a tiny bit to arrive at what appears to an elegant solution. Moving the corner columns inward a bit is the solution that interferes with the pattern the least, keeps all the metopes the same width, and looks natural.

So, it seems logical that logic was relaxed just a tiny bit to arrive at an elegant solution.

These subtle features set the Parthenon apart from all other Greek temples because the overall effect is a departure from the static Doric structures of the past, towards a more dynamic form of architectural expression. Moreover, the intricate refinements of the forms required unprecedented precision that would be challenging to achieve even in our time.

But it was not mere grandeur through subtlety that the Athenians desired. It is evident that they sought to out-shine all other temples of the time through the choice of decadent marble, refined precision, measured proportions and imposing dimensions. Above all, the Parthenon dazzled with its colors and patterns, and with the lavish sculptural decoration that crowned the top perimeter of the temple.

The Sculptures of the Parthenon

As a temple, the Parthenon’s main function was to provide shelter for the monumental chryselephantine (gold and ivory) statue of Athena. A temple in Ancient Greece was literally “the house” of the deity/ies it was dedicated to. The statues were considered to be the presence of the deity which resided in the main cella.

Its Doric exterior was decorated with an abundance of sculptures. It includes the traditional Doric frieze on the exterior entablature (the band above the columns that goes around the building) that was decorated with alternating metopes and triglyphs, and a continuous frieze on the exterior wall of the cella (the exterior wall of the temple’s interior), which is commonly seen on temples of the Ionic order.

The pediments of the Parthenon were decorated with elaborate marble statues dedicated to mythological aspects of Athena. The sculptures of the pediment were monumental in size and arranged in dynamic compositions that filled the confined triangular spaces efficiently.

Learn more about sculptures of the Parthenon…

The Colors of the Parthenon

The colors of the Parthenon have washed away over the past 2400 years, but pigment remnants can still be traced on certain surfaces, so we know that the building was colored. But was every surface covered in color? Were the colors vivid, soft like pastel, or a wash like watercolor? We can not be certain.

Several different interpretational drawings have been produced since the 19th century CE. Scholars like Durm, Loviot, Paccard,, Semper, Springer, Windstup, created conflicting educated reproductions, some with vivid, some with bright, and some without much color. But even in their divergence, they provide some guidance on the placement and type of colors used.

Analysis of the temple’s pigment remnants by the Acropolis Restoration Service in 2024 revealed that the flat background of the tested metopes contains remnants of red and red-orange pigment, while the flat bands that frame each at the top and bottom have remnants of blue, including Egyptian blue on the top band. (Αγγελακοπούλου, 1:01:18).

Pigments used on marble in ancient times were derived from colored earth (red, red-orange, yellow, brown ochre), minerals (azurite, malachite, conichalkite, and cinnabar), and chemicall processes (Egyptian blue, lead white, minium, carbon black).

We know some of the colors that were used on the Parthenon and its sculptures, but we don’t have much information on the precise process, the degree of pigment saturation in the binder, or the actual paint application style, so we cannot be sure what the overall final visual effect of colored temple was.

Learn more about the Parthenon Colors…

Parthenon Context

As a “post and lintel” temple, the Parthenon presents no engineering breakthrough in building construction. However its stylistic conventions have become the paradigm of Classical architecture, and its style has influenced architecture across the globe for many centuries after it was built.

The Parthenon is a large temple, but it is by no means the largest one in Greece. Its aesthetic appeal emanates from the refinement of many established norms of Greek architecture, and from the quality of its sculptural decoration.

Some of these details were found in other Greek temples while some were unique to the Parthenon. The temple owes its refined appeal to the subtle details that were built into the architectural elements to accommodate practical needs or to enhance the building’s visual appeal.

The Parthenon epitomizes all the ideals of Greek thought during the apogee of the Classical era through artistic means.

The idealism of the Greek way of living, the attention to detail, as well as the understanding of a mathematically explained harmony in the natural world, were concepts dear to the Athenians.

These ideals are represented in the perfect proportions of the building, in its intricate architectural elements, and in the anthropomorphic statues that adorned it.

The Athenian citizens were proud of their cultural identity, and conscious of the historical magnitude of their ideas. They believed that they were civilized among barbarians, and that their cultural and political achievements were bound to alter the history of all civilized people. The catalyst for all their accomplishments was the development of a system of governance the likes of which the world had never seen: Democracy.

Democracy, arguably the epitome of the Athenian way of thinking, was at center stage while the Parthenon was built. This was a direct democracy where every citizen had a voice in the common issues through the Assembly that met on the Pnyx hill next to the Acropolis forty times per year to decide on all matters of policy, domestic or foreign.

Unseen hitherto, common people are depicted as individuals on the decorative frieze of the temple, something that is seen by scholars as a symbol of the elevated importance of the individual citizen.

One of the defining characteristics of western civilization, “the individual” in Classical Greece was recognized as a significant entity and a considerable moving force in the polis and the observable universe. It was therefore natural to accept that common citizens were a worthy subject of sacred iconography–even mingling with the gods as seen on the Parthenon frieze.

A Cinematic Approach

The Parthenon was conceived in a way that the aesthetic elements allow for a smooth transition between the exterior and the interior where the chryselephantine statue of Athena was housed.

A visitor to the Acropolis who entered from the Propylaia would be confronted by the majestic proportion of the Parthenon in three quarters view, in full sight of the west pediment and the north colonnade.

As the visitor moved closer to the temple, the details of the sculpted metopes would become decipherable, and when in proximity to the base of the columns, parts of the frieze would become evident in tantalizing colorful glimpses peering from sun-deprived spaces, high on the cell wall and between the columns.

Moving towards the east and looking up towards the exterior of the cella, a visitor would be mesmerized with the masterful depiction of the Panathenaic procession as it appeared in cinematic fashion on the frieze. Each vignette would be visually interrupted by the Doric columns of the exterior similar to modern film frames. Except, in the Parthenon’s case, it would be the viewer moving instead of the frames.

The Panathenaic procession was certainly a scene that every Athenian could relate to through personal experience, making thus the transition between earth and the divine a smooth one.

Eventually, as the visitor moved farther east, they would turn right at the corner to face the entrance of the Parthenon. There, high above the columns and the entablature, on the east pediment they would marvel at the sculptures that depict nothing less than the birth of Athena. Just beyond this dramatic central scene, they would see the earthly arrephores folding the peplos among the other Olympian gods and heroes of the frieze.

Then, just below, the “peplos” scene, through the immense open doors, any visitor would be enchanted by the glistening gold and ivory hues of the monumental statue of Athena glistening at the back of the dim cella.

It seems certain that the master planners of the Parthenon conceived it as a theatrical event. The temple was constructed with the movements of the viewer in mind, and by the arrangement of the temple, the monumental sculptures of the pediment, and the detailed frieze, the emotions of the visitors were choreographed to prepare them for the ultimate glimpse of the majestic Athena Parthenos in the interior of the naos, and to maximize the effect of an awe inspiring visit.

The Cost of the Parthenon

The Parthenon construction cost the Athenian treasury 469 silver talents. While it is almost impossible to create a modern equivalent for this amount of money, it might be useful to look at some facts. One talent was the cost to build one trireme, the most advanced warship of the era, and “…one talent was the cost for paying the crew of a warship for a month” (D. Kagan, The Peloponnesian War, 61). According to Kagan, Athens at the beginning of the Peloponnesian war had 200 triremes in service, while the annual gross income of the city of Athens at the time of Perikles was 1000 talents, with another 6000 in reserve at its treasury.

Parthenon Facts

Year Built: 447-432 BCE

Precise Dimensions:

Width East: 30.875 m

Width West: 30.8835 m

Length North: 69.5151 m

Length South: 69.5115 m

Width to Length Ratio: 9:4

Width to height Ratio (without the Pediments): 9:4

Number of stones used to built the Parthenon: Approximated at 13400 stones.

Project supervisor: Phidias

Architects: Iktinos and Kallikrates

Parthenon Cost: 469 talents

Coordinates: 37.9715° N, 23.7267° E

Parthenon Photos

Parthenon Timeline

447-432 BCE: The current version of the Parthenon was built.

267 CE: Herulian Invasion: Destruction of Athenian Monuments, followed by more destruction from Vandals, and Visigoths shortly thereafter.

Circa 300 CE: The Parthenon underwent hasty repairs that redressed and refitted blocks of stone for different purposes.

6th Century: Converted into a Christian church. Sections of the frieze were removed to create windows for the church.

1180: Church renovations removed the central section of the entablature, including the central scene of the east frieze and pediment to create an enlarged apse.

1205: The Parthenon became a Latin Church.

1458: The Parthenon was converted into a Muslim mosque.

1687: Explosion after bombardment in the Turkish-Venetian war left the Parthenon largely in the state we see it today.

1800-1805: The Italian painter, Lugeri, working for Lord Elgin, caused extensive destruction to the Parthenon by dislodging and sawing off parts of the ancient building as he removed the sculptures known as “The Elgin Marbles”.

1834: The Acropolis became an archaeological site.

1842-1844, 1900-1902, 1913, 1922-1933: Restoration of the Parthenon.

1940, 1954-60: Restoration of the Parthenon.

(Korres)